Copyright 2016 by Gary L. Pullman

Feuds don't always end in death, and many involve words rather than weapons. Often, feuds produce animosity and emotional trauma. Sometimes, they destroy personal or professional reputations. Occasionally, they put an end to a person's career.

No

one seems immune to the feelings that ignite feuds, and such

conflicts have involved writers, a philosopher, artists, inventors,

psychoanalysts, patriots, scientists, and sharpshooters. One involved

even a former U. S. secretary of state and a sitting vice-president.

Hopefully,

we'll never become involved in extended hostilities such as those in

which the individuals of these 10 famous feuds participated.

10 Hans Christian Andersen vs. Charles Dickens

10 Hans Christian Andersen vs. Charles Dickens

Both

Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) and Charles Dickens (1812-1870)

greatly admired one another's work. They met during Andersen's 1847

tour of England, and a 10-year period of “friendly correspondence”

ensued. When the Danish author again visited England, he stayed as a

guest in Dickens' home, Gads Hill Place. His visit was supposed to

last two weeks but stretched, instead, to five, disrupting the

Dickens' household and vexing the English author's children. Subtle

hints that it was time to end his visit went unnoticed.

After Andersen finally departed, Dickens wrote a note on the guestroom mirror: “Hans Andersen slept in this room for five weeks—which seemed to the family AGES!” Andersen, who'd “thoroughly enjoyed” his stay, was confused when Dickens broke off their correspondence. Some contend Dickens, as an act of revenge, modeled “the bony bore” Uriah Heep of his novel David Copperfield on Andersen.

After Andersen finally departed, Dickens wrote a note on the guestroom mirror: “Hans Andersen slept in this room for five weeks—which seemed to the family AGES!” Andersen, who'd “thoroughly enjoyed” his stay, was confused when Dickens broke off their correspondence. Some contend Dickens, as an act of revenge, modeled “the bony bore” Uriah Heep of his novel David Copperfield on Andersen.

9 Hans Christian Andersen vs. Søren Kierkegaard

Hypersensitive

to criticism concerning his work, Andersen often “retaliated” by

writing caricatures of his critics. In 1838, when Danish philosopher

Søren Kierkegaard wrote an unsympathetic review of Andersen's only

novel, Only a Fiddler (1837), Kierkegaard ignited a feud with

his fellow Dane. Describing the novel as uneven and unoriginal and as

failing to separate the author from his characters, Kierkegaard's

generally negative review suggested the fiddler's grievance with life

represented Andersen's own “dissatisfaction with the world” and

his reluctance to struggle in life.

In “The Snail and the Rose-bush” (1863), Andersen may have retaliated by depicting the rather reclusive Kierkegaard as a snail—and a female one, at that—who comes out of her shell only once a year to question a rose-bush (Andersen) about why it flowers (creates art), before retreating again into her solitude. The snail, Andersen's narrator says, “had much within her, she had herself” and regarded the world as “nothing.”

In “The Snail and the Rose-bush” (1863), Andersen may have retaliated by depicting the rather reclusive Kierkegaard as a snail—and a female one, at that—who comes out of her shell only once a year to question a rose-bush (Andersen) about why it flowers (creates art), before retreating again into her solitude. The snail, Andersen's narrator says, “had much within her, she had herself” and regarded the world as “nothing.”

8 Leonardo da Vinci vs. Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni

Both

celebrated artists even in their own day, Leonardo da Vinci

(1452-1519) and Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni

(1475-1564) were rivals whose feud seemed to be inspired by mutual

jealousy. Michelangelo publicly insulted Leonardo, “shocking

bystanders when he sneered at the older genius for never finishing

his statue of a horse in Milan.” Attending a meeting to decide

where Michelangelo's statue of David

should stand, the older artist suggested the genitals of

Michelangelo's sculpture should be covered, his comment suggesting “a

symbolic castration of his rival.

7 Thomas Edison vs. Nikola Tesla

7 Thomas Edison vs. Nikola Tesla

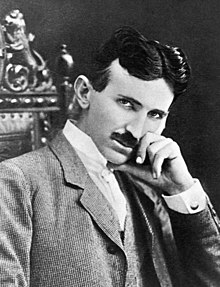

NikolaTesla (1856-1943) hoped to impress Thomas Edison (1847-1931) with his

work on alternating current (AC), but Edison, committed to his own

work on direct current (DC), brushed him off. Thereafter, Tesla sold

his patents to Edison's rival, George Westinghouse (1846-1914), for

whom Tesla went to work. Westinghouse was already working on AC at

the time, but Tesla “helped to improve upon the process and the

product.” A highlight in the feud between Tesla and Edison occurred

with the so-called War of the Currents, which Tesla and Westinghouse

won.

6 Thomas Edison vs. George Westinghouse

6 Thomas Edison vs. George Westinghouse

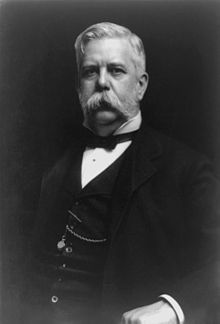

Westinghouse

had the financial clout needed to take on Edison, and, in him, Edison

recognized a threat, as Westinghouse Electric “began

installing its own AC generators around the country, focusing mostly

on the less populated areas that Edison’s system could not reach”

while, at the same time, the company undercut the fees Edison charged

his urban customers for electricity.

Edison

believed AC was “dangerous.” To demonstrate its lethal effects,

Edison began electrocuting dogs, claiming AC would kill a human being

just as quickly. Later, he also electrocuted “several calves and a

horse,” and, when Harold Brown (1857-1944), an electrical engineer

and electricity salesman, was commissioned to build an electric chair, Edison bribed him to use AC. William Kemmler's (1860-1890)

execution was botched, and the murderer died horribly, his face

“contorted,” a palm bloody from his clenched fist, and his coat

on fire. Witnesses were horrified, and Westinghouse feared losing

millions if Edison convinced people AC was deadly.

Edison

next arranged to electrocute an elephant, Topsy, who'd been

determined to represent a danger to people. The execution took place

at Coney Island and featured the use of AC. Despite Edison's efforts

to convince the public that DC was safer than AC, Westinghouse won a

contract to illuminate the World's Fair and received “all the

positive publicity he would need to make alternating current the

industry standard.”

5 Sigmund Freud vs. Carl Jung

5 Sigmund Freud vs. Carl Jung

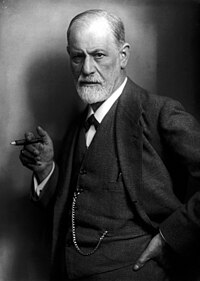

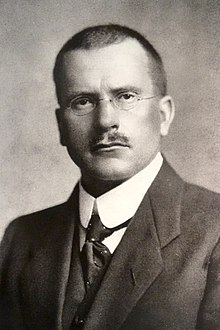

Psychoanalysis'

founder, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), and Carl Jung (1875-1961), who

originated analytical psychology, differed in their views about the

nature of the unconscious. Their differences fueled a feud marked by

“charges and counter-charges. Freud fainted several

times while in Jung's presence. Freud says Jung harbored death wishes

towards him; Jung laughed the idea off.” Supposedly, both men also

recognized the development of homosexual feelings for one another,

which may have facilitated their parting of ways.

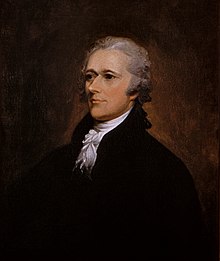

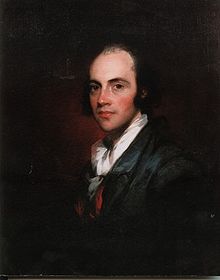

4 Alexander Hamilton vs. Aaron Burr

4 Alexander Hamilton vs. Aaron Burr

The

longstanding feud between former U. S. Secretary of the Treasury

Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804) and Vice-President Aaron Burr

(1756-1836) ended in an illegal duel on July 11, 1804, in which

Hamilton was killed. They had several political rivalries, but their

feud climaxed with “the New York governor's race in 1804.” Burr,

until then a Republican, ran as an independent candidate. Hamilton

encouraged New York Federalists “not to support Burr,” and Burr

lost the election. “A relative slight” gave Burr the excuse he

needed, and he challenged Hamilton to a duel. Each man fired his

pistol. Burr remained unharmed, but Hamilton suffered a mortal wound,

dying the following day. Although Burr survived the duel, his career

as a politician was a casualty of the affair, and he never held

“elective office again.”

3 Patrick Henry vs. Thomas Jefferson

3 Patrick Henry vs. Thomas Jefferson

Patriot

Patrick Henry (1736-1799) and Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) became

embroiled in a protracted feud when Jefferson believed “that Henry

was critical of his performance as Governor during the Civil War.”

Although,

when “he was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1768,”

Jefferson “joined its radical bloc, led by Patrick Henry and George

Washington,” Jefferson's later two years as Virginia's governor

marked “the low point” of Jefferson's political career,” as

“torn between the Continental Army's desperate pleas for more men

and supplies and Virginians' strong desire to keep such resources for

their own defense, Jefferson waffled and pleased no one.” In

addition, to protect his state's capital from the British army, he

moved it from Williamsburg to Richmond, “only to be forced to

evacuate that city when it, rather than Williamsburg, turned out to

be the target of British attack.” He further humiliated himself

when, the day before his second gubernatorial term, he “was forced

to flee his home at Monticello” to evade “the British cavalry,

thereby incurring the label of coward. Henry's criticism of his term

in office offended Jefferson, and the two men feuded thereafter.

2 Thomas Henry Huxley vs. Richard Owen

2 Thomas Henry Huxley vs. Richard Owen

English

Victorian anatomist and paleontologist Richard Owen (1804-1892), the

assistant curator of the Royal College of Surgeons' Hunterian

Collections, refused to accept Charles Darwin's (1809-1882) theory of

evolution. Instead, he held that each species is derived from the

same archetypal “blueprint” created by God. Owen's views brought

him into conflict with Darwin's “bulldog,” Thomas Henry Huxley(1825-1895), resulting in a feud between the men that lasted

throughout their respective careers. Their debate as to whether the

brains of apes and men were more similar (Huxley's view) or

dissimilar (Owen's position) reached its climax when Huxley

“conclusively demonstrated that the hippocamus minor, a small fold

at the back of the brain,” was not “unique to man,” as Owen

insisted, “but also was to be found in the brains of apes.” The

British public, which followed the claims of the rivals with great

interest, judged Huxley to have won their long-standing feud.

Nevertheless, Owen's distinguished career continued until he retired

at age 79.

1 Annie Oakley vs. Lillian Smith

1 Annie Oakley vs. Lillian Smith

Buffalo

Bill's Wild West Show wasn't big enough for both Annie Oakley

(1860-1926) and Lillian Smith (1871-1930). Oakley, called “Little

Sure Shot,” and Smith, dubbed “the California Huntress,” were

both expert shots, but Oakley was regarded as “demure, feminine and

reserved, while Smith was seen as flirtatious, brash and boastful.”

Newspaper accounts of their exploits played up the differences in

their personalities and in their respective ages: Oakley was 11 years

Smith's senior, but Oakley insisted she was 6 years younger than her

actual age. Smith suggested her rival's celebrity was fading. Unlike

Oakley, Smith also received the benefit of the doubt when the same

behavior by both of them was called into question. While touring

England, Oakley scandalized the nation when she shook hands with

“Prince Edward's first wife,” but Smith, who did likewise,

received no reprimand. Buffalo Bill Cody also flamed the fires of

their feud by praising Smith's skills “while downplaying Oakley's

achievements.” Finally, Oakley left the show. Ultimately, though,

Oakley's fame continued, whereas Smith's career ended in obscurity.

(LINK 15)

.jpg/220px-Miguel_%C3%81ngel%2C_por_Daniele_da_Volterra_(detalle).jpg)

.jpg/220px-Official_Presidential_portrait_of_Thomas_Jefferson_(by_Rembrandt_Peale%2C_1800).jpg)

.jpg/220px-T.H.Huxley(Woodburytype).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment