Copyright 2016 by Gary L. Pullman

"To

be defeated is pardonable; to be surprised—never!”—Napoleon

Bonaparte

The

sneak attack—aggressors view it as a smart military maneuver, while

victims see it as an unsportsmanlike act of cowardice. It’s no

wonder, then, that a sneak attack is likely to result in a

declaration of war, followed by a full-blown conflict.

Despite

the strategic advantage an attacker achieves by a surprise strike,

provoking an enemy with a sneak attack does not always ensure victory

in the long run. Of the ten examples of war-inciting sneak attacks

listed below, an equal number of countries or groups who fell prey to

sneak attacks turned the tables on their attackers and won the

ensuing war.

10

Invasion of Plataea: Second Peloponnesian War (431 BC)

The

Second Peloponnesian War opened with Thebes' sneak attack on Plataea

in 431 BC.

According

to the Athenian historian and general Thucydides, Naucleides and his

fellow traitors within the gates of Plataea hoped to gain power for

themselves by assisting the city's enemies. They opened the city's

gates to Theban troops during the night. No Plataean guard had been

posted, as the attack had been prearranged with the approval of

Eurymachus, a citizen of great influence among the Plataeans.

Anticipating

war with Plataea, Thebes wanted to conduct a preliminary surprise attack, and this was the means chosen to accomplish this objective.

Once the Theban troops entered the city, they stacked their weapons

in the marketplace. They refused to kill whoever opposed Thebes'

control of their city, as Naucleides and his confederates had

intended. Instead, the invaders invited the Plataeans to join them

voluntarily, in allegiance to Thebes.

At

first, the Plataeans agreed, but, when they discovered they

outnumbered the invaders, they decided to overcome them, if possible.

To avoid being detected, they tunneled through common walls to

gather. They had placed wagons in the streets to form barricades. At

first light, the Plataeans rushed from their houses, attacking the

enemy. Surprised by the sneak attack, the Theban troops resisted,

driving their attackers back several times. However, the Plataeans

continued to press their attack, aided by women and slaves, who, from

inside their houses, “pelted them with stones and tiles.”

It

had rained throughout the night. The streets were muddy. The gate

through which the Theban soldiers entered had been shut and barred.

Many of the troops did not know any other way out of the city. The

early morning light was dim, “the darkness caused by the moon being

in her last quarter.” The Plataeans, familiar with their city and

its streets, were able to intercept them as they fled, the Thebans'

courage failing them.

Some

of the troops climbed the city's wall and jumped, often to their

deaths. One party found a “deserted gate” and broke it open with

an ax taken from a woman, but only a few escaped, having been spotted

by the Plataea's citizenry. Other bands of the enemy were 'cut off”

as they fled. A large body of the troops rushed into a building

adjacent to the city wall, mistaking it for access to a gate. As the

citizens debated as to the best course of action to take, some

suggesting the building be burned down around the invaders, Thebans

surrendered unconditionally. However, many others of them had been

killed.

In

all, the Theban troops numbered 300, under the command of Pythangelus and Diemporus, both Boeotarchs. A contingent had remained in Thebes,

as reinforcements. When news of their failed invasion reached them,

they marched at once to aid their comrades in arms. However, Thebes

was eight miles north of Plataea, the roads were thick with mud due

to the previous night's rain, and the Asopus river had risen and was

difficult to ford. By the time they reached their destination, the

Plataeans had killed or captured all of the advance force.

To

acquire hostages, the Theban reinforcements intended to kidnap local

shepherds and other workers in the fields nearby. Through a herald,

the Plataeans informed the Theban soldiers that, should they harm any

of their fellow citizens, they would kill their 108 captives.

According to the Thebans, if they withdrew from the area, the

Plataeans would release their prisoners unarmed. However, the

Plataeans insist that they agreed only to negotiate with the Thebans

if they withdrew, never promising to release their captives. Once the

Theban troops withdrew, the Plataeans gathered their men from the

countryside and then put their captives to death.

The

Theban troops' sneak attack on Plataea failed, but it ignited the

Second Peloponnesian War, as Plataea's ally, Athens, began

hostilities against the Peloponnesians, led by Sparta.

9

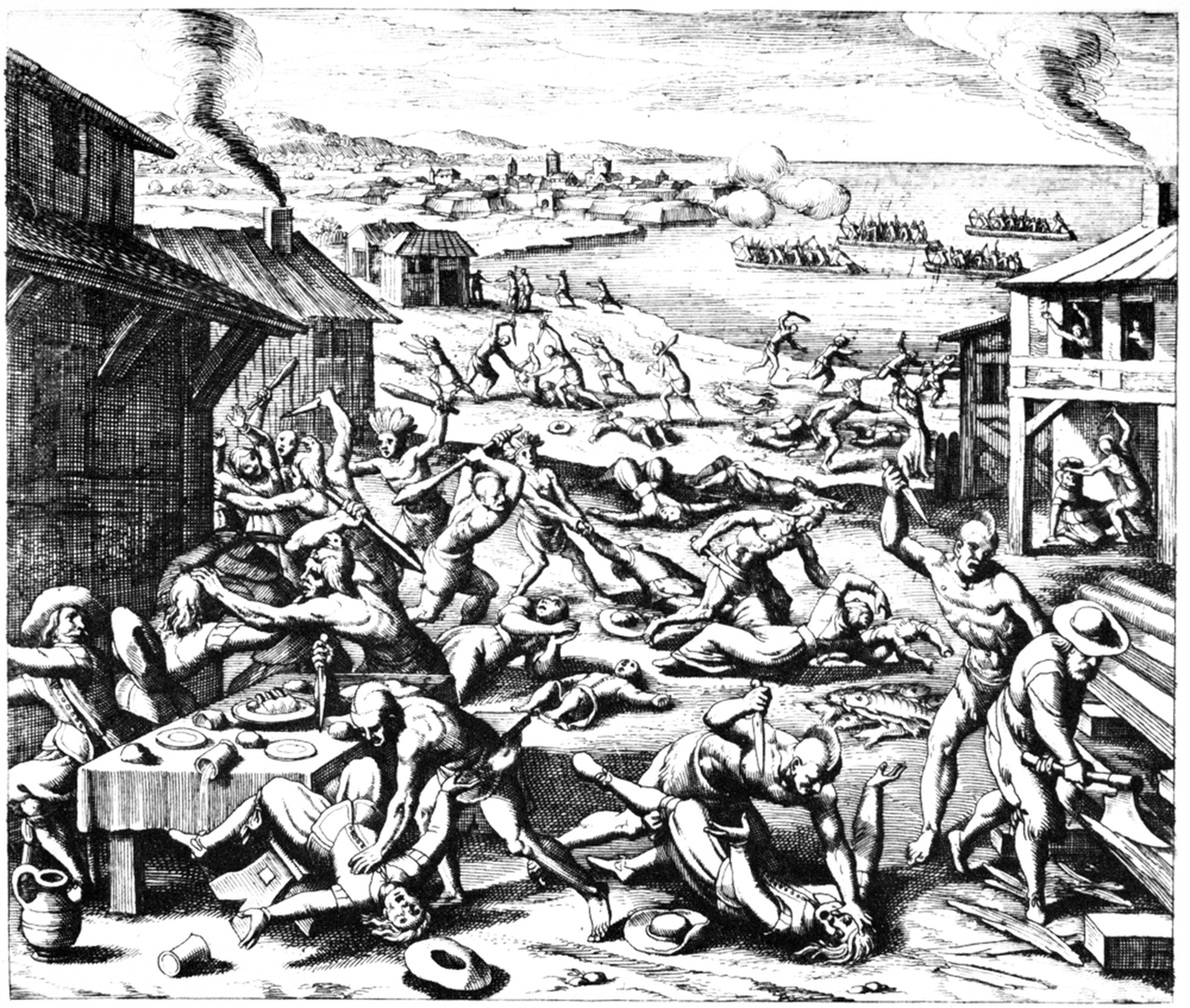

Attacks on Colonial Settlements: Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1622)

The

Second Anglo-Powhatan War lasted 10 years, from 1622-1632. The

belligerents were English colonists in Virginia and the 28 to 32

“Algonquian-speaking” tribes of “Indians of Tsenacomoco, who

were “often called the Powhatan Indians, in honor of their

paramount chief.” The Indians were “led by Opitchapam and his

brother (or close kinsman) Opechancanough.”

The

war started when “Opechancanough led a series of coordinated

surprise attacks that concentrated on settlements upriver from

Jamestown.” As a result of these lightning-swift strikes, “nearly

a third of the English population” was killed. The attacks having

come “as a complete shock” to the colonists, they were unable to

defend themselves and were soon overcome. In many cases, their

corpses were “mutilated.”

The

cause of these attacks was the encroachment of the colonists on

Indian territory as they moved “up the James River.” The Indians'attack was intended both to repel the colonists and to demonstrate

the Indians' “supremacy over the newcomers.”

The

colonists' ultimate victory was gained not through military might,

but by the destruction of the Indians' food supplies, the acres and

acres of corn they relied on for survival.

The

Indians made a tactical error in not pressing “their advantage,”

and the colonists mounted a prolonged and determined campaign against

their adversaries, “repeatedly” attacking “their food supply.”

The colonists calculated the Indians' food loss was enough to have

fed 4,000 individuals.

Agreeing

to a truce with the Indians so that both sides could plant their new

corn crops, the colonists toasted the agreement after providing the

Indians with poisoned wine. After killing them, the colonists scalped

some of the dead. When a full-scale battle in 1624 ended in

stalemate, the colonists destroyed more of their adversaries' crops,

repeating this tactic for five more years, until Virginia's “new

governor finally assigned an agreement” that ended the war.

8

Attacks on Acton Farms and Lower Sioux Agency: U. S.-Dakota War

(1862)

The

U. S.-Dakota War of 1862 “ended with hundreds dead. The Dakota people exiled from their homeland and the largest mass execution in

U. S, history: the hangings of 38 Dakota men in Mankato on Dec. 26,

1862.” It, too, began with a sneak attack.

Treaties

between the U. S. government and the Dakota nation called for the

Dakotas to cede land to the United States in return for annuities and

funds for “trade shops (such as blacksmiths), . . . agricultural

tools and supplies” and the payment of “debts claimed by

traders.” However, the Dakotas claim that these alleged debts were

false or “inflated” and objected “to the traders being paid

directly by the U. S. government,” The situation created bad blood

between the United States and the Dakotas, as did the government's

attempt to force the Dakotas to “acculturate,” rather than retain

their own way of life.

Times

were hard, and, when annuities were not paid on time, some traders

and Indian Agency employees refused to extend credit to the Dakotas.

These broken promises and this ill treatment precipitated the war,

when Taoyateduta led a band of Dakotas in an attack on the Lower

Sioux Agency, killing many civilians, following an attack, the

previous day, in which “four Dakota men killed five people” on

two farms in Acton. The Dakotas followed the sneak attack with

assaults on other towns and army posts. The resulting “war lasted

six weeks” and cost the lives of more than 600 civilians and U.S.

soldiers, as well as an estimated 75-100 Dakota, who lost their

lives.”

Even

after the war, “intermittent fighting” continued between the

Dakota Indians and the United States throughout the 1880s, until it

culminated in the Battle of Wounded Knee, on December 29, 1890.

7

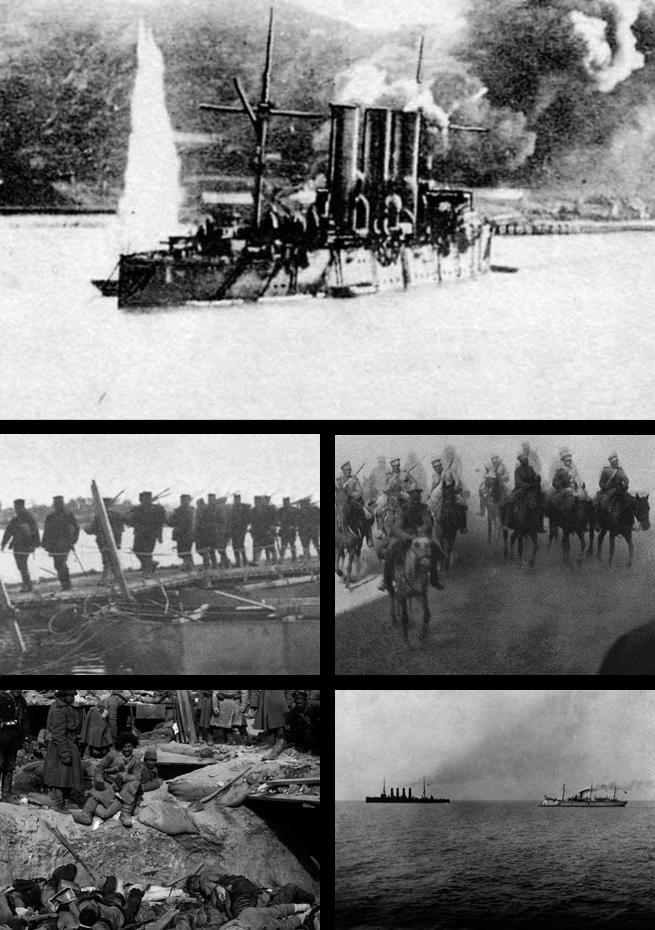

Attack on Port Arthur: Russo-Japanese War (1904)

Japan

had decided to attack.

It

had steadily built up its army, over the 10 years since its 1894 war

with China, and, now, as a result, it enjoyed a “marked

superiority” over its former adversary. Russia might occupy

southern Manchuria's Liaotung Peninsula, and it might have “extended

the Trans-Siberian Railroad across Chinese-held Manchuria,” but

China was vulnerable. It still lacked the assets needed supply “its

limited armed forces in Manchuria.” Russia's refusal to withdraw

troops from Manchuria, as it had agreed to do, gave Japan the excuse

it needed.

On

February 8, 1094, Japan's main fleet “launched a surprise attack

and siege on the Russian naval squadron at Port Arthur.” A month

later, Japanese troops “overran” Korea. Two months after this,

Japan landed another army on the Liaotung Peninsula, cutting Port

Arthur off “from the main body of Russian forces in Manchuria.”

Russian troops retreated before an advance of Japanese soldiers, and

Russia's subsequent attempt to take the offensive proved

“indecisive.”

In

1905, Port Arthur's commander surrendered, and the Russians lost the

war's final land battle at Mukden. The Japanese victory in the

maritime Battle of Tsushima was a turning point, and their victory

over Russia's Baltic Fleet in the Battle of Tsushima Strait that

followed brought Russia to its knees. Japan had won the war, thanks,

in part, to its sneak attack on Port Arthur.

6

Attack on Royal Irish Constabulary: Irish War of Independence (1919)

“The

only way to start a war was to kill someone, and we wanted to start a

war.”

So

said Dan Breen, a member of The Irish Republican Army (IRA), who took

part in the 1919 sneak attack that left two members of the Royal

Irish Constabulary dead—and started the Irish War of Independence.

The

mood was right, in Ireland, at this time, for independence from

Britain. Leaders of the Easter Rising, or Easter Rebellion, had been

executed. Sínn Féin had a “won 70% of the total Irish seats in

the 1981 General Election.” Refusing to recognize the authority of

the British Parliament, they established their own government body,

the Dáil Éireann (Assembly of Ireland), in Dublin, “to govern Ireland from Ireland.”

To

start the war of independence they longed for, “IRA members in

Tipperary ambushed and killed two unarmed members of the Royal Irish

Constabulary.” They got what they wanted, as Britain moved to put

down the rebellion.

Against

the wishes of his fellow Sínn Féin colleagues, commander MichaelCollins ordered the IRA to conduct guerrilla warfare tactics, using

sneak attacks to surprise “small groups of British troops” with

“quick ambush attacks” so their victims would not have the

opportunity to defend themselves.

Britain

responded by organizing two groups, the Black and Tans (so called

because of the colors of their uniforms) and the Cairo Gang. The

former, consisted of conscripted World War I veterans, whose mission

was to “keep order in Ireland.” The former, made up of “former

secret agents and spies,” were assigned the tasks of taking “down

the IRA networks in Ireland.”

Using

“informers within the British forces” and a “squad” of secret

assassins, Collins ordered the executions of high-ranking British

officials and secret agents. The worst incident of the war, Bloody

Sunday, occurred on November 21, 1920, when the IRA dispatched

multiple operatives “to several addresses in Dublin to assassinate

members of the Cairo Gang . . . . killing fourteen of them and one

member of the Black and Tans.”

The same day, the Royal Irish

Constabulary and the Black and Tans “opened fire on a crowd at a

Gaelic football match at Croke Park, killing 14 members of the

public, including a woman and a child, and injuring dozens more.”

The

violence was not yet over. The same evening, “three imprisoned IRA

members were tortured and killed at Dublin Castle after allegedly

trying to escape.”

Terroristattacks on police and the public alike resulted in 1,000 deaths

within six months (January 1921 through July 1921).

The

war ended when Collins, accompanied by IRA negotiator Arthur

Griffiths, signed a treaty with British officials, agreeing to end

the conflict in exchange for Ireland's independence as “a dominion

of the British Empire.” Many IRA members did not accept the terms

of the treaty, however, and a civil war ensued.

5

Attack on Pearl Harbor: World War II (1941)

The

very idea that the 1941 Japanese assault on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, was

a sneak attack is controversial. Many believe that the so-called

secrecy of the attack was due to nothing more than “fateful

accidents and plain bumbling that delayed the delivery of a document

to Washington hinting at war.”

Indeed,

some conspirators go so far as to insist that U. S. president

Franklin Delano Roosevelt knew full well of the Japanese plans, in

advance of the attack, but intentionally sat idly by, allowing the

Pearl Harbor attack to occur, as an excuse for the United States to

declare war on Japan and enter World War II.

Historians

and government officials typically contend that communications

problems and

diplomatic red tape prevented the United States from knowing about

Japan's war plans: “Textbookshave

dwelt on the problems of transmission and translation of the

so-called Final Memorandum, on Dec. 7, 1941—the day Pearl Harbor

was attacked,” and other “accounts have focused on the slowness

of the Japanese Embassy in Washington to produce a cable of the

memorandum from Tokyo, and on delays caused by security rules

prohibiting the embassy's American secretary from typing the

document.”

However,

relatively recently discovered “diplomatic papers” seem to show,

quite clearly, a “picture . . . of a breathtakingly cunning deceit

by Tokyo aimed at avoiding any hint to the Roosevelt administration

of Japan's hostile intentions.” Furthermore, according to Takeo Iguchi, “the researcher who discovered the papers in the Foreign

Ministry archives, the draft memorandum, together with the wartime

diary of Japan's general staff,” indicate “a vigorous debate

inside the [Japanese] government over how, indeed whether, to notify

Washington of Japan's intention to break off negotiations and start a

war.” Meanwhile, as Japanese military commanders debated the issue,

their government's “diplomats in Washington [were] deliberately

kept in the dark by their capital,” while they met “with their

American counterparts.”

''The

diary shows that the [Japanese] army and navy did not want to give

any proper declaration of war, or indeed prior notice even of the

termination of negotiations,'' says Iguchi. ''And they clearly

prevailed.'' Iguchi says, further, that “the general staff,

together with a pliant Foreign Ministry, had controlled not only the

content of the message to Washington, but also its timing,” so that

the message was not to be “delivered to the State Department”

until “1 p.m. Washington time on Dec. 7.” Secretary of State

Cordell Hull did not receive the message until “about 2:20 p.m.,

approximately one hour after the sinking of the American Pacific

Fleet at Pearl Harbor.” The

famous delay in delivering the message, he said, was probably the

result of deliberate planning,” The

New York Times

declares.

The

sinking of the American navy fleet at Pearl harbor seems, clearly, to

have been the result not of a plan known in advance by President

Roosevelt or any other U. S. official, civilian or military, but a

deliberate sneak attack. From the perspective of the U. S., it

started a war which, four years later, Japan and its allies, the Axis

Powrs, lost.

4

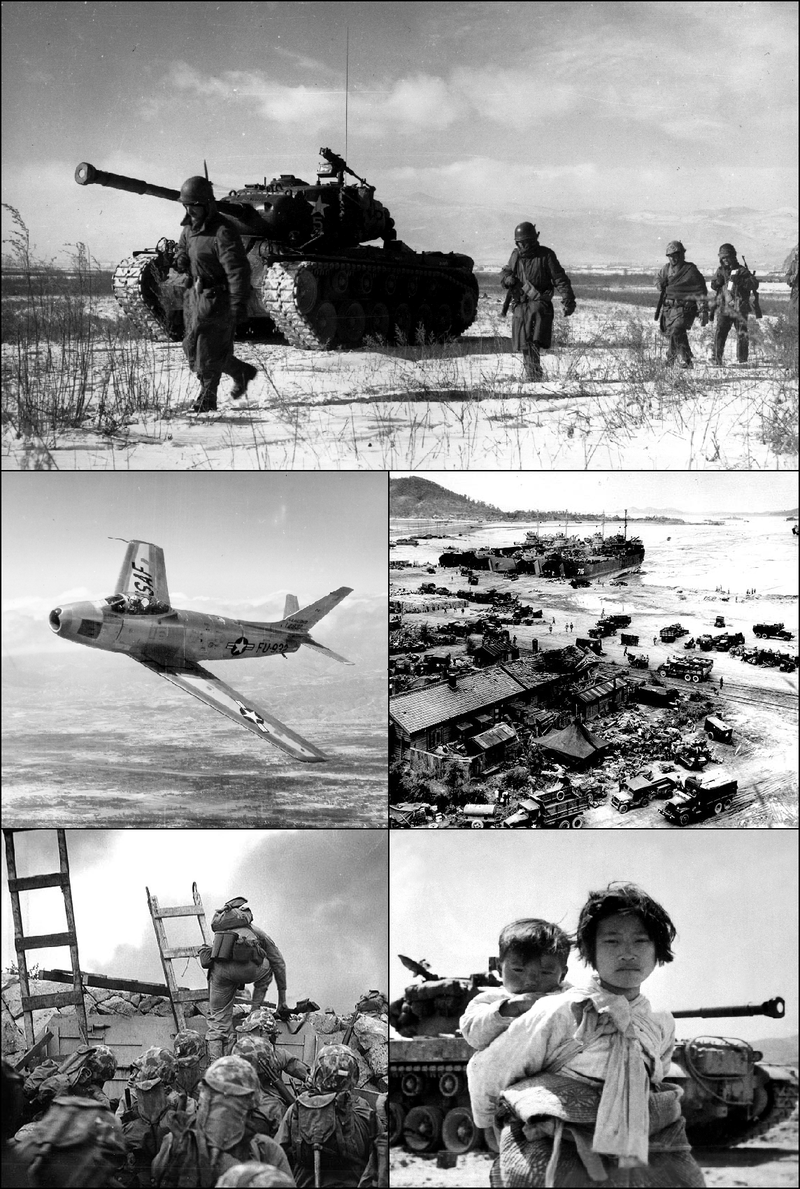

Invasion of South Korea: Korean War (1950)

Although,

in general, the events of the Korean War are familiar to most, many

are unaware that it began with a sneak attack.

The

circle of latitude 38 degrees north of the equator (known as the

“38thparallel”) marked the border between North Korea and South Korea,

so, when the North

Korean People's Army (NKPA)

,

without provocation, crossed this line on June

25, 1950,

they invaded their southern neighbor. This incident started the

Korean War.

“Eight

divisions and an armored brigade (90,000 soldiers) . . . attacked in

three columns,” catching the Republic of Korea (ROK) off guard. The

ROK's 98,000-man army's training was “incomplete,” and, with “no

tanks and only 89 howitzers” at its command, South Korea's military

forces were “no match for the better-equipped,” battle-hardened

NKPA. The ROKA was “overwhelmed” and retreated “south in

disarray,” leaving Seoul vulnerable to the invaders, who captured

South Korea's capital city.

President

Harry S. Truman authorized General Douglas MacArthur to “use all

forces available to him” to protect Pusan. After securing Pusan,

MacArthur landed troops at Inchon, perceiving that the NKPA became

“more vulnerable to an amphibious envelopment” the farther south

they invaded. MacArthur liberated Seoul after “street-to-street

fighting,” returning it to South Korean control. Truman ordered

MacArthur to invade North Korea, taking the fight to the enemy.

Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) entered the war in support of North

Korea.

The

war became, more and more, a stalemate, and “armistice negotiations

began on July 10, 1951, at Kaesong.” Although CCF intensified its

attacks during peace negotiations, the armistice was signed on July

27, 1953, and all hostilities ceased. More than 33,600 American

military personnel were killed in the war, and over 103,000 were

wounded. Enemy forces suffered 1,500,000 casualties, prisoners

included, among whom 900,000 were Chinese.

The

greatest war, so far in the history of the world that had begun with

a sneak attack, was finally over. It ended ambiguously, with neither

opponent a clear victor.

3

Attack on Egypt: Six-Day War (1967)

One

of the world's shortest wars also began with a sneak attack.

On

May 22, 1967, Egypt blockaded the Straits of Tiran, preventing ships

from sailing to or from Israel's southernmost port at Eilat. As a

result, Israeli's single “supply route with Asia” was cut off, as

was “the flow of oil from” Israel's “main supplier, Iran.”

Although

the United Nations, the United States, and other countries supported

Israeli's “right of access to the Straits of Tiran,” and the

United States tried to negotiate with Egypt, Egypt signed a “defense

pact” with Jordan, and Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser stated

that “the armies of Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon are poised on

the borders of Israel . . . to face the challenge, while standing

behind us are the armies of Iraq, Algeria, Kuwait, Sudan and the

whole Arab nation.” The “Arabs,” he declared, were “arranged

for battle.” Iraq's president, Abdur Rahman Aref, also voiced his

nation's support of Egypt and its allies, calling for the eradication

of Israel: “The existence of Israel is an error which must be

rectified,” he said. “This is our opportunity to wipe out the

ignominy which has been with us since 1948. Our goal is clear—to

wipe Israel off the map.”

Surrounded

by hostile nations apparently bent on his Israeli's destruction and

aware that his nation's military forces could not remain “fully

mobilized indefinitely,” as they had been for three weeks, and

refusing to “allow its sea lane through the Gulf of Aqaba to be

interdicted,” Israel decided to launch a sneak attack on its

adversaries.

The

United States refused to become involved, declaring itself “neutral

in thought, word and deed,” and “imposed an arms embargo on the

region,” as did France, while the Soviets supplied “arms to the

Arabs” and “the armies of Kuwait, Algeria, Saudi Arabia and Iraq

were contributing troops and arms to the Egyptian, Syrian and

Jordanian fronts.” Isolated, Israel launched a massive sneak

attack, dispatching all but a dozen of its Air Force fighters.

(Twelve remained behind to guard “Israeli airspace.”)

The

plan was to attack “while the Egyptian pilots were eating

breakfast.” As a result of this surprise assault, 300 Egyptian

aircraft were destroyed within two hours, and “by the end of the

first day, nearly the entire Egyptian and Jordanian air forces, and

half the Syrians’, had been destroyed on the ground.” The air

assaults were followed by ground battles in which Israeli and

Egyptian tanks fought it out “in the blast-furnace conditions of

the Sinai desert.”

When

Israeli fighters returning to Israeli after destroying Egyptian air

force assets on the ground were suspected of launching an attack

against Jordan, King Hussein ordered the bombardment of Jerusalem,

causing an exodus of Palestinian refugees into Jordan from the West

Bank. Having defused the threat to its existence and seeking to avoid

a confrontation with the Soviets, who had threatened to intervene on

behalf of Israel's opponents, Israeli accepted a cease-fire on June

10. Casualties on both sides were high, as was the loss of military

assets, but Israel had survived and had tripled the size of its

territory, and a military administration was established, rather than

Israel's annexing the West Bank.

2

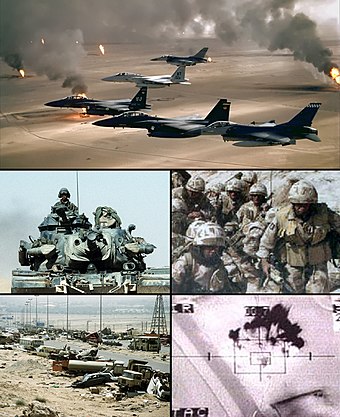

Invasion of Kuwait: Gulf War (1990)

In

a sneak attack, Iraqi president Saddam Hussein ordered “an army of

more than 100,000 soldiers and 700 tanks to cross the Iraqi border

into Kuwait at 1 a.m. on August 2, 1990.” Aided by air and sea

support, these forces approached Kuwait City “from two directions.”

Two days after this surprise attack, Kuwait was overwhelmed, and the

Iraqi occupation began. When the international community condemned

the invasion, Hussein warned that he would make a “graveyard” of

Kuwait if any other nations intervened on its behalf. Six days later, he announced his intention of annexing Kuwait as

Iraq's “19th

province.”

When

Hussein ignored calls for him to withdraw from Kuwait, U. S.

president George Bush “issued an “ultimatum on August 28.” If

Iraqi forces did not “withdraw within 48 hours,” war would be

declared. Hussein ignored the warning, and Iraqi forces began to

prepare fortifications and barriers “along the coast and Saudi

border.” Hussein also threatened to destroy Kuwait's oil wells and

other infrastructure.

Operation

Desert Shield began on August 7 and lasted until January 16, 1991,

when Operation Desert Storm commenced. The latter lasted for six

weeks and involved massive air attacks by Stealth fighters and other

aircraft firing stand-off missiles. ( (A guided missile has

“stand-off capability” if it can be fired from an aircraft at a

great enough distance from its target to be out the range of enemy

defenses.) The U. S. sneak attack on Iraqi air defenses removed the enemy's air

defense capability, helping ground forces move aggressively, without

fear of being attacked from the air by Iraqi warplanes.

Hussein

lived up to his threat to destroy Kuwait's oil wells and “pumped

oil into the Gulf.” Within a month, “hundreds of oil wells were

ablaze and 1.5 million barrels per day of oil were pouring into the

Gulf.” Hussein also attempted, unsuccessfully, to invade Khafji, a

Saudi Arabian town.

After

Hussein defied another ultimatum to withdraw from Kuwait, a ground

war, Operation Desert Sabre, commenced. Coalition forces entered

Kuwait from the south and dispersed throughout the country. Iraqi

forces sought to abduct Kuwaiti citizens and continued to lay waste

to the oil fields and to buildings and other structures they'd

“pre-wired with explosives.” A Kuwaiti resistance group

“barricaded themselves in a house in Kuwait City's Al-Qurain

district and battled” Iraqi tanks but were defeated after 10

hours. On February 26, Hussein ordered his troops to withdraw. Two

days later, “coalition forces, led by Kuwaiti soldiers, entered the

ruins of Kuwait City,” and the war was over. On March 15, the

exiled emir returned to Kuwait to resume governing the nation.

1

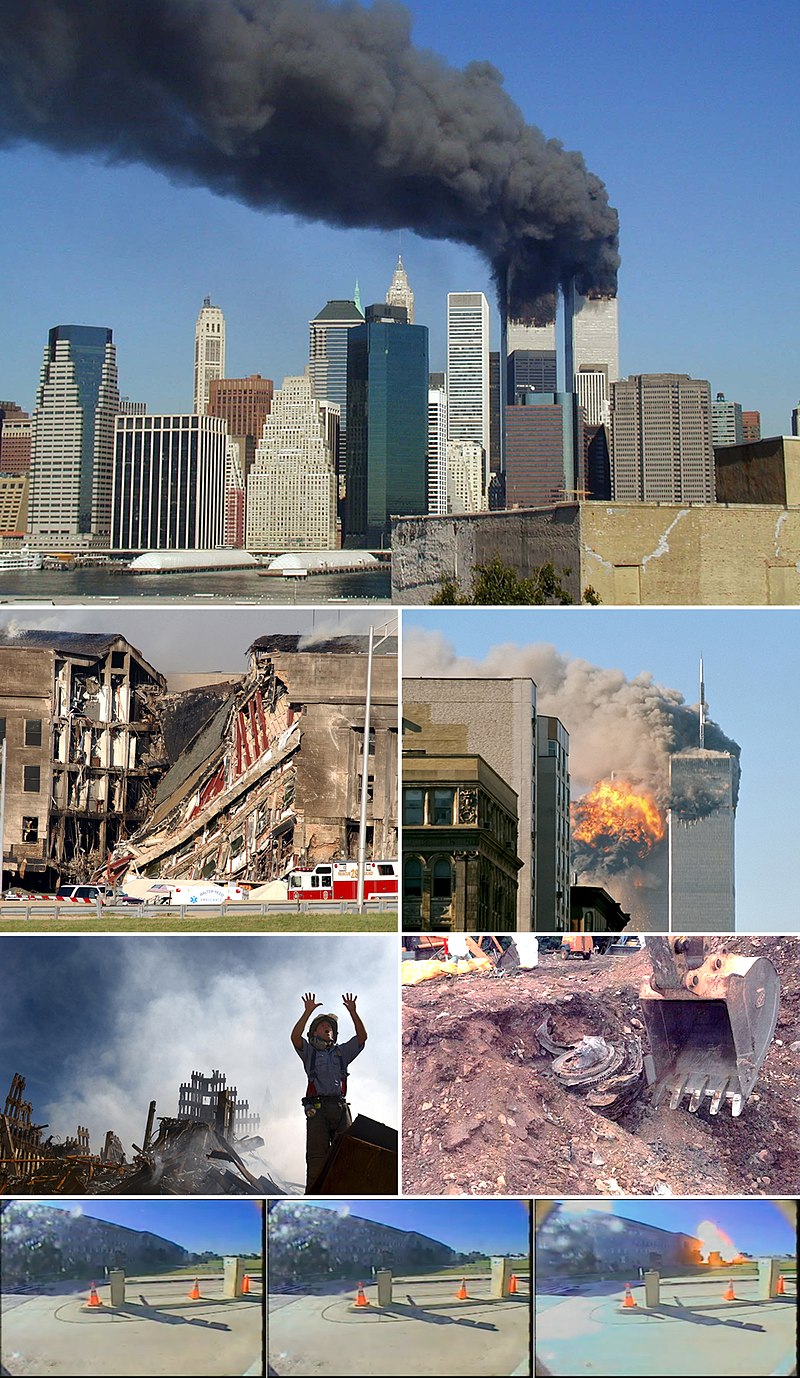

Attacks on The World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and Flight 93: War

on Terror

Various

conspiracy theories seek to account for the terrorist attacks that

took place in the United States on September 11, 2001. Although there

are quite a few such theories, some of the more common ones are that

“someone . . . other than Al Qaeda orchestrated the events of 911,”

that “the Twin Towers collapsed because of a controlled substance,”

that “a missile, not a plane, hit the Pentagon,” and that Flight

93 was shot down by a missile over Pennsylvania.”

The

truth of the matter is that 19 Al Qaeda terrorists from Middle

Eastern nations conducted secret attacks on three locations: the

World Trade Center, in New York City, New York; the Pentagon, in

Arlington, Virginia; and a commercial aircraft, which crashed in

Shanksville, Pennsylvania. The airliner had been hijacked by

terrorists and is believed to have been en route to Washington, D.

C., where it would be used to destroy the White House or the Capitol

Building.

These

sneak attacks against unarmed civilians resulted in the U. S.

invasion of Afghanistan, in 2001, and ignited the Iraq War, which

began in 2003. Intelligence reports indicated that the Taliban, a

terrorist organization running the government in Afghanistan, “was

protecting Al Qaeda's leader [Osama] Bin Ladin and allowing Al Qaeda

to run training camps in the country.” Intelligence reports also suggested that Iraq was concealing weaponsof mass destruction to which terrorists might receive access.

(Contrary to these reports, no such weapons were found.)

As

a result of the invasion of Afghanistan, the Taliban were deposed,

and many Al Qaeda operatives have been captured or killed. Bin Laden

himself was killed in Pakistan in 2011 by U. S. military forces.

Hussein

was also captured. He was later put to death by an Iraqi court.

Despite

the military efforts of the coalition forces, the War on Terror

continues.

.jpg/424px-World_Trade_Center%2C_New_York_City_-_aerial_view_(March_2001).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg/1920px-Basilosaurus_cetoides_(1).jpg)

.jpg/800px-Martin_Schongauer%2C_The_griffin_(15th_century).jpg)