Copyright 2016 by Gary L. Pullman

For

the most part, we take our bodies for granted. Unless there's a pain

or some other indication that there's a problem, we are usually

pretty much unaware of our flesh and blood and bone. However, in

short stories written by the likes of H. P. Lovecraft, H. G. Wells,

Edgar Allan Poe, Ray Bradbury, Stephen King, and other masters of

horror and fantasy, characters not only pay attention to, but often

become obsessed with, the body—or, more specifically, with parts of

the body.

In such stories, body parts often have lives of their own. They inspire evil deeds. They suggest madness, guilt, or hubris. They involve characters—and readers—in a spiritual realm beyond the material universe we often, perhaps mistakenly, regard as the only real world.

These stories about body parts may make us think differently the next time we look at ourselves in the mirror.

(Caution: Spoilers ahead.)

In such stories, body parts often have lives of their own. They inspire evil deeds. They suggest madness, guilt, or hubris. They involve characters—and readers—in a spiritual realm beyond the material universe we often, perhaps mistakenly, regard as the only real world.

These stories about body parts may make us think differently the next time we look at ourselves in the mirror.

(Caution: Spoilers ahead.)

10 Edgar Allan Poe's “The Tell-Tale Heart”: A Story

About a Human Eye

Edgar Allan Poe's short story “The Tell-Tale Heart” was published in the January 1843 issue of James Russell Lowell's The Pioneer.

In the story, the first-person narrator recounts the motive for the crime he committed, his commission of the crime itself, and his confession of the crime to the police.

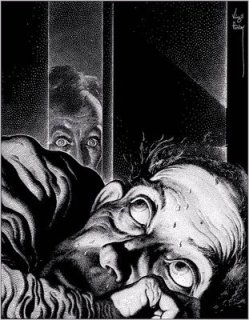

Although the narrator insists he is not mad, his own account of his crime suggests otherwise. He kills his victim because he saw the old man's eye as a hideous, filmed-over, “vulture-like” orb. However, he says he loved the old man himself. Except for his horror at the sight of the old man's eye, there's no explanation for the murder he commits. His motive is emotional, not rational. Because his victim's eye appalls him, the narrator decides to kill him.

Obsessed with disposing of the eye, the narrator spends a week rehearsing themurder. Each night his will falters, but his determination is revived again by the sight of the old man's eye, even when it is closed in sleep. However, with the eye closed, the narrator is unable to commit the deed. “I found the eye always closed; and so it was impossible to do the work; for it was not the old man who vexed me, but his Evil Eye.”

On the eighth night, the narrator finds his victim's eye open and is outraged, terrified, and obsessed at the offending orb.

In

“The Tell-Tale Heart,” an innocent victim's eye prompts a madman

to murder him.

9 Edgar Allan Poe's “The Tell-Tale Heart”: A Story

About a Human Heart

“The Tell-Tale Heart” is also a story about a human heart. Even before the mad narrator kills his innocent victim, he begins to hear—or fancies he hears—the old man's heart beating wildly with terror. Having heard the narrator's thumb slip upon the lantern's “tin fastening,” the old man suspects someone is lying in wait to do him harm. The sadistic narrator waits, allowing his victim's terror to mount. His heartbeat accelerates even more, until it sounds as though his “heart must burst.” Concerned a neighbor might also hear the old man's heart, the narrator acts. Overturning his bed upon his victim, the narrator either crushes or smothers him.

Although he places his hand on the old man's heart to ensure he is dead and feels “no pulsation,” the heart again beats wildly after the narrator disposes of it. Dismembering the body, he conceals its pieces beneath the floorboards of the old man's bedroom. Now, he becomes as obsessed with the sound of the wildly beating heart as he had been, before the murder, with the old man's “vulture” eye. When he can bear to hear it no longer, he confesses to the police who, tipped off about a scream in the night, come to investigate the incident.

8 H.

G. Wells' “Pollock and the Porroh Man”: A

Story About a Human Head

Herbert George (H. G.) Wells' short story “Pollock and the Porroh Man” was published in the anthology The Plattner Story and Others in 1897.

After the protagonist of the story kills the Porroh man's woman, the Porroh man (a fakir, or “witch-doctor”) seeks revenge. He attempts to kill Pollock, by gunfire and by dispatching snakes. To protect himself, Pollock hires a man to kill his adversary. Soon after, the assassin brings him the Porroh man's decapitated head. Perera, a trader with whom Pollock temporarily stays while in Sulyma, suggests the Porroh man may have put a spell on Pollock before he was killed. Pollock buries the Porroh man's head, but a dog digs it up and leaves it in Pollock's hammock, where he is shocked to see it the next morning.

Next, Pollock casts the head into the river, but it washes ashore. Its finder, who tries to sell it to Pollock, leaves it behind, in Pollock's shed, frightened by Pollock's obvious fear of it. Finding the head, Pollock attempts to burn it on a bonfire. The captain of the steamer taking him to Bathurst finds it “smoked” on the beach. He takes it aboard his ship, telling Pollock about his discovery. Pollock continues to have nightmares about the head, which somehow manages to follow him wherever he travels.

A physician recommends Pollock try a “miracle cure.” When Pollock, who is not religious, declines, the doctor suggests he “go in search of stimulating air,” to “Scotland, Norway, [or] the Alps.” Pollock takes the doctor's advice, but, wherever he goes and whatever he does, he continues to see the Porroh man's head and to have nightmares about it. Finally, on Christmas morning, recalling his “vicious,” selfish life and the grotesque, gruesome head that haunts him, Pollock takes his ownlife.

7

H. P. Lovecraft's “Herbert West—Reanimator”: A Story About a

Human Head

Howard

Phillips (H. P.) Lovecraft's short story “Herbert West—Reanimator”

was published, in six installments, in the February through July,

1922, issues of George Julian Houtain's magazine HomeBrew.

West, believes the human body is a machine that can be restarted, should it expire. He has developed a reagent he believes will reanimate it. To prove his hypothesis, West needs corpses. He obtains them in various ways. He pays men to rob graves. He steals the corpse of a recently deceased accident victim. He helps himself to the bodies of typhoid victims. He steals a boxer's cadaver. He acquires the body of a salesman who died from a heart attack. He claims the corpses of dead World War I soldiers while serving as a medic.

Several years later, West concentrates on reanimating body parts, rather than entire bodies. When his commanding officer, a fellow medic, Major Sir Eric Moreland Clapham-Lee, dies, West has the chance to try another experiment. He discards the major's body. It is unusable, because of injuries from the airplane crash in which Clapman-Lee died. Keeping only the dead man's head, he puts it in a vat and injects it with his experimental serum. The reanimated head shouts at the body to “jump.” West's lab is destroyed in a bomb attack, and he assumes the headlessbody and the severed head were lost in the blast.

After the war ends, West rents a house joined to catacombs. He reads a newspaper account of a band of strange-looking men led by a man with a wax head. As he reads, he is confronted by the same men. They are an army of zombies, led by Clapman-Lee's body, which is fitted with a wax head. (Clapman-Lee's actual head, it is implied, is in the box one of the zombies carries and speaks for its body, in the manner of a ventriloquist.) West orders the box burned. As it does, the zombies enter his home, through the catacombs, and disembowel Wells. Clapman-Lee's corpse then decapitates the reanimator, before retreating with his army.

West, believes the human body is a machine that can be restarted, should it expire. He has developed a reagent he believes will reanimate it. To prove his hypothesis, West needs corpses. He obtains them in various ways. He pays men to rob graves. He steals the corpse of a recently deceased accident victim. He helps himself to the bodies of typhoid victims. He steals a boxer's cadaver. He acquires the body of a salesman who died from a heart attack. He claims the corpses of dead World War I soldiers while serving as a medic.

Several years later, West concentrates on reanimating body parts, rather than entire bodies. When his commanding officer, a fellow medic, Major Sir Eric Moreland Clapham-Lee, dies, West has the chance to try another experiment. He discards the major's body. It is unusable, because of injuries from the airplane crash in which Clapman-Lee died. Keeping only the dead man's head, he puts it in a vat and injects it with his experimental serum. The reanimated head shouts at the body to “jump.” West's lab is destroyed in a bomb attack, and he assumes the headlessbody and the severed head were lost in the blast.

After the war ends, West rents a house joined to catacombs. He reads a newspaper account of a band of strange-looking men led by a man with a wax head. As he reads, he is confronted by the same men. They are an army of zombies, led by Clapman-Lee's body, which is fitted with a wax head. (Clapman-Lee's actual head, it is implied, is in the box one of the zombies carries and speaks for its body, in the manner of a ventriloquist.) West orders the box burned. As it does, the zombies enter his home, through the catacombs, and disembowel Wells. Clapman-Lee's corpse then decapitates the reanimator, before retreating with his army.

6 Edgar Allan Poe's “Berenice”:

A Story About Human Teeth

Poe's short story “Berenice” was published in the March 1835 issue of The Southern Literary Messenger, a magazine edited by Poe himself.

In the story, the narrator, a young man named Egaeus, plans to marry his cousin Berenice, with whom he has grown up in his father's mansion. Both characters suffer from an illness, one mental, the other physical. He describes his own condition as one in which he may “muse for long unwearied hours,” until he loses “all sense of motion or physical existence.” He describes Berenice's affliction as “a species of epilepsy not unfrequently terminating in trance itself—trance very nearly resembling positive dissolution.” From this “trance,” her recovery, Egaeus adds, “was, in most instances, startlingly abrupt.” In contemporary psychological terms, Egaeus has monomania, fixating on objects, while Berenice suffers from a mysterious disease, a symptom of which is catalepsy.

As the date of their marriage approaches and Egaeus is in the library, Berenice, in one of her “trances,” appears before Egaeus. She displays all the appearances of death. Due to his monomania, he becomes obsessed with her teeth. Egaeus' obsession torments him to the point of madness. He believes that only by possessing her teeth can he restore his reason.

Some time after Berenice leaves the library, a servant tells Egaeus she has died and must be buried. Later, awakening in a confused state, he finds his clothing bloodstained. During a state of catalepsy, she was mistaken for dead. Egaeus has opened Berenice's grave and extracted his beloved's teeth—while she was yet alive.

5 Ray Bradbury's “Skeleton”: A

Story About a Human Skeleton

Ray Bradbury's short story “Skeleton” was published in the September, 1945, issue of Weird Tales.

The story opens as the protagonist, Mr. Harris, visits his physician, Dr. Burleigh, for the tenth time “this year.” He is concerned about his aching bones. Dissatisfied with his doctor's diagnosis, hypochondria, Mr. Harris next consults M. Munigan, who advertises himself as a “bone specialist,” although he has no medical degree. Receiving no satisfaction from Munigan, Mr. Harris returns home. Still fixated on his skeleton, he examines his bones. Although his wife Clarisse assures him his skeleton is fine, he continues to “brood” over it. Whether at work or at home, he obsesses over the fact there's a skeleton inside him. He even begins to imagine his bones are imprisoning his organs, clamping and “squeezing” his brain and his heart.

It dawns on Mr. Harris that his skeleton is as much under his control as he is under its. When his bones attack him, causing him to lose weight, he strikes back by denying his skeleton the calcium it needs. However, he fears he may be down to skin and bones in no time. He decides to take a business trip, as Munigan had earlier suggested. However, he runs his car off the road and returns home, “psychologically” prepared, at last, for Munigan's help. Munigan debones him, leaving him a gelatin-likemass of unsupported flesh calling his wife's name.

4

F. Marion Crawford's “The Screaming Skull”: A Story About a Skull

F. Marion Crawford's short story “The Screaming Skull” was published in the 1911 issue of Wandering Ghosts.

Captain Charles Braddock, the story's protagonist-narrator, inherits property from his cousin Pratt. Pratt's body was found with its throat torn out, lying on a beach next to a box containing a skull. The skull was returned to the house, where both Braddock and his servants often hear it scream. Perhaps the screams have something to do with Pratt's having murdered his wife. He'd spooned molten lead into her ear after Braddock told him how another man had used this means to kill his own spouse. Braddock fears the murdered woman may have avenged herself upon Pratt. He also fears she may intend to kill him because he'd suggested to Pratt the means to kill her.

Although he tries to rid himself of the skull, it makes its way back to the house. A skeptic, Braddock refuses to believe in the supernatural, even though he suspects the ghost of Pratt's wife may be trying to kill him. He imprisons the skull in its box, seals the lid shut with wax, and stores it inside a locked cupboard in the bedroom Pratt and his wife shared.

The story ends with a newspaper account of Braddock's “strange death.” He is found with his throat torn out. The teeth marks identify his killer as a human, presumed to be “an escaped maniac.” The killer, the coroner's report adds, is thought, because of the size of the jaws, to be a woman.

In a note at the end of the story, Crawford informs his readers that his tale is based on “legends about a skull which is still preserved in the farmhouse called Bettiscombe Manor, situated. . . on the Dorsetshire Coast.”

3

Stephen King's “The Moving Finger”: A Story About a Human Finger

Stephen King's short story “The Moving Finger” was published in the December, 1990, issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. It was also published in King's 1993 collection of short stories Nightmares & Dreamscapes.

When Howard Mitla is confronted with a mysterious finger poking out of his bathroom drain, he fears the monstrous digit may attack him. Determined to get rid of the intruder, he uses a drain cleaner. When this tactic fails, he tries to chop it off with electric hedge trimmers.

Although Mitla is finally successful in disposing of the finger, King's story ends with the observation that “there are more fingers than one on a hand.”

2 Clive Barker's “The Body Politic”: A Story About Human Hands

“The Body Politic” is the first short story in Volume Four of Clive Barker's series of collected tales of horror, The Books of Blood, which were published by Sphere Books in 1984 and 1985.

In this satirical story, human hands are conscious. They resent being controlled by the bodies to which they are attached, as possessions rather than as independent and self-governing beings in their own right. The outraged hands of a factory worker named Charlie start a revolution—after strangling Charlie's wife, Ellen.

However, Charlie's hands have strong personalities and do not see eye to eye. Left exercises caution. Right, on the other hand, is something of a firebrand. The differences in their personalities leads Right to sever his relations—literally—with Left, and he chops off his unfortunate brother. Left then organizes other hands, and a revolution against the rest of the bodies gets underway.

1

W. W. Jacobs' “The Monkey's Paw”: A Story About a Monkey's Paw

William Wymark (W. W.) Jacobs' short story “The Monkey's Paw” was published in 1902, in both Harper's Magazine and in a collection of his stories called Our Lady of the Barge.

During a rainstorm, Mr. and Mrs. and their son Herbert are visited by Sergeant-Major Morris. He shows tells them a mummified monkey's paw—a magic charm he obtained from an Indian fakir. To prove people's lives are “ruled” by fate, the fakir “put a spell on” the paw. It allows three wishes to be granted to three of its successive owners. As he considers his own experience with the paw, Morris throws it into the s' fire. “Better let it burn,” he warns his hosts, but Mr. retrieves it from the flames. He uses it to wish for 200 pounds.

The next day, Herbert is killed in an accident at his factory. His parents are awarded 200 pounds. A week after Herbert's mutilated body is buried, Mrs. remembers the monkey's paw, She has her husband use it to wish their son alive again. Some time later, a knock sounds at their door. Mrs. rushes downstairs to admit their son. However, Mr. , aware that wishes linked to the monkey's paw always seem to go wrong, is horrified at the thought of “the thing” pounding on his door. He scrambles to retrieve the monkey's paw as his wife climbs onto a chair to reach the bolt locking the door. Just as she draws the bolt, he finds the monkey's paw and makes his last wish. No one is at the door. His wife's “wail of disappointment and misery” emboldens Mr. . He runs to the front gate, where he sees “the street light flickering . . . on a quiet and deserted road.”